HOME | DD

TrollMans — Viscerous Flukebird

TrollMans — Viscerous Flukebird

Published: 2024-03-01 21:15:50 +0000 UTC; Views: 27501; Favourites: 253; Downloads: 17

Redirect to original

Description

Obligate parasitism as a lifestyle is one of extreme specialization, as the environment of a living animal is one unlike any other ecosystem, one that perpetually provides easily accessible sustenance but also actively attempts to rid itself of the freeloader. Many of the adaptations used for surviving the outside world are redundant or unnecessary By this metric, it should be no surprise that the squicks, a lineage of birds highly specialized over tens of millions of years for obligate parasitism, have become some of the most derived theropods to have ever lived, with forms scarcely even vertebrate in appearance. And of those, possibly the most freakish of any bird that has ever evolved are the ones which have managed to evolve to thrive deep within the viscera of another. Progressing from scavenging larva to skin-burrowing pests to creatures living much further into the flesh was not as drastic a progression as it may seem, as such adaptations occurred amongst invertebrates more than once.

Aside from their size, skuorcs are more susceptible to internal parasites than the thorngrazers, and, to a lesser extent, trunkos, that once dominated the ecology of Serinarcta because their digestive process is much more inefficient and their process of ingestion is crude, with no chewing involved, allowing oral intake of parasites to occur much more easily. The vast gut of a skuorc is enlarged; because there is no mechanical digestion of ingested matter, it relies almost entirely on extended bacterial fermentation in large gastric chambers to leech out absorbable nutrients in vegetation, meaning there is plenty of real estate. Squicks were able to migrate from life as a skin parasite to embedding themselves into the lining of the mouth, crop, stomach, and deeper reaches of the digestive system, feeding on blood or stealing semi-digested matter from their host, until they are eventually excreted naturally. Living inside an animal may require certain distinct adaptations, but it means they no longer need to worry about being dug out by parasite-eaters. This subgroup of squicks, known as flukebirds, are widespread amongst larger herbivores and omnivores, particularly skuorcs, and generally harmless unless in particularly heavy infestations in unlucky individuals. Most only spend part of life lifespan as gastric endoparasites, emerging in the dung as fattened larvae which burrow into the earth, pupate, and emerge as typical adult squicks. Although, a few species have adapted to life almost permanently nestled deep inside the guts of another.

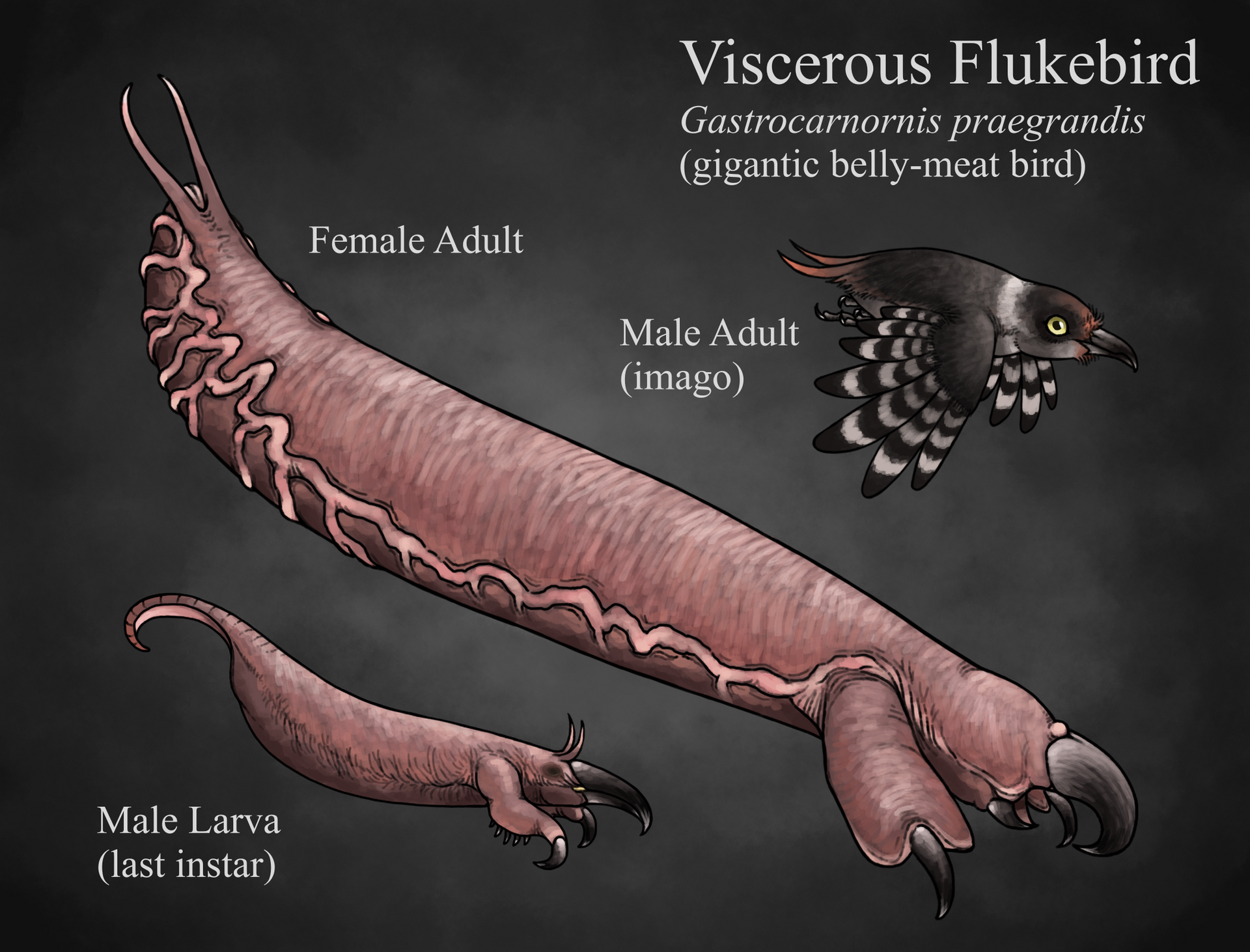

The skin of the flukebirds have numerous defences to avoid being digested, a very thin layer of translucent keratin (which most animals have difficulty processing) over a large portion of the skin, a constant secretion of mucus, and enzymes in the mucus which neutralize digestive juices. The bones of the rudimentary skeleton are almost entirely cartilaginous, the respiratory system is basically vestigial, and the digestive tract is simple. Most oxygen and nutrient intake occurs through folds of the permeable skin simply by diffusion, and the skin along the flanks is very loose and wrinkled to greatly increase surface area, allowing for a greater rate of osmosis. A hooked beak and clawed forelimbs are retained to keep the squick securely attached against the forces of peristalsis, for independent movement through the digestive organs, and for finding a suitable cocooning location once ejected to complete its metamorphosis. Since eyesight is useless, flukebirds have developed an enlarged vomeronasal organ-like structure at the base of the beak to detect changes in the chemical changes, other flukebirds, or competing parasites.

The viscerous flukebird is a particular species with massive sexual dimorphism, with the female having highly neotenous development, never naturally maturing past the fleshy, grub-like infantile stage of its life, only increasing in size greatly. Indeed, a full-grown viscerous flukebird female, capable of growing just over a foot long from vent to beak-tip, is the largest of all the squicks, although the male is much, much smaller than her. Both males and females begin their life-cycle similarly, developing in the stomach lining by feeding on blood; the female eventually migrates to the small intestine, where she latches on to a suitable spot in the gastrointestinal wall for the rest of her life, which can last for years. The male too, eventually migrates to the small intestine, but not to feed, to seek out a female. The male has particularly large and forked sensory organs to find her inside the intestine; necessary since he is stumbling totally blind inside an intestine can stretch for more than two-hundred feet. If no female can be detected, he can wait in a state of dormancy in a mucous chrysalis for several months until one shows up, and small spines along his arms give him extra grip for crawling through the bowels. The male will mount himself to the back of a female, his squeezing motions and the sensation of the small spines inducing the female to release an egg sac (numerous tiny jelly-like eggs within a thin membrane), which he grasps with his flattened curling tail, and carries with him as he then exists the digestive tract. When he burrows into the ground to pupate, he buries the eggs alongside him in the pupal chamber. Once he emerges as a mature feathered, flighted animal, he will fertilize and then ingest the egg sac, storing it in his crop (as he does not eat as an adult, his digestive system is now non-functional).

Some flukebirds deposit their dormant eggs on vegetation or carrion their preferred hosts are likely to ingest, or inside various well-used watering holes, in the hopes that some of the eggs will make their way into the suitable animal, but the viscerous flukebird has a more proactive dispersion technique. The male will fly directly onto a gantuan or skulossus, and loosely glue eggs onto its skin, targeting the back, neck, and forelimbs. Then the eggs will wait until they are accidentally ingested when the animal grooms itself (or, in skulossi, when a herd-mate grooms them) with its mouth, allowing them finally activate and hatch inside the stomach. Once the egg sac is emptied, the male viscerous flukebird will die of starvation, usually within one week of emergence. Males of some other flukebird species do feed after maturation and will live much longer (although just comparatively, up to a few months), searching out dung of their hosts to find other egg sacs to fertilize and carry off; the dung of infected hosts have a scent noticeable only to them, making potentially egg-containing faeces easier to find. This strategy is much more energy-intensive for the female as it includes the very high likelihood that many eggs are wasted, and requires males to manually search for eggs, resulting in a far greater uncertainty he will live to pass on his genes. While the viscerous flukebird has a more complex reproductive strategy and each male only insures one batch of progeny, the likelihood of young from this one batch succeeding to reach maturity is much more likely.

---

This post could be seen months earlier on Patreon ; consider subscribing if you'd like to support me!

Related content

Comments: 6

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 7 ⏩: 0

👍: 9 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 6 ⏩: 0

👍: 5 ⏩: 0